Two years before Shenzhen was named mainland China’s first special economic zone in 1980, Hong Kong industrialist Cheng Ho-ming arrived to start working with a state-run wig factory.

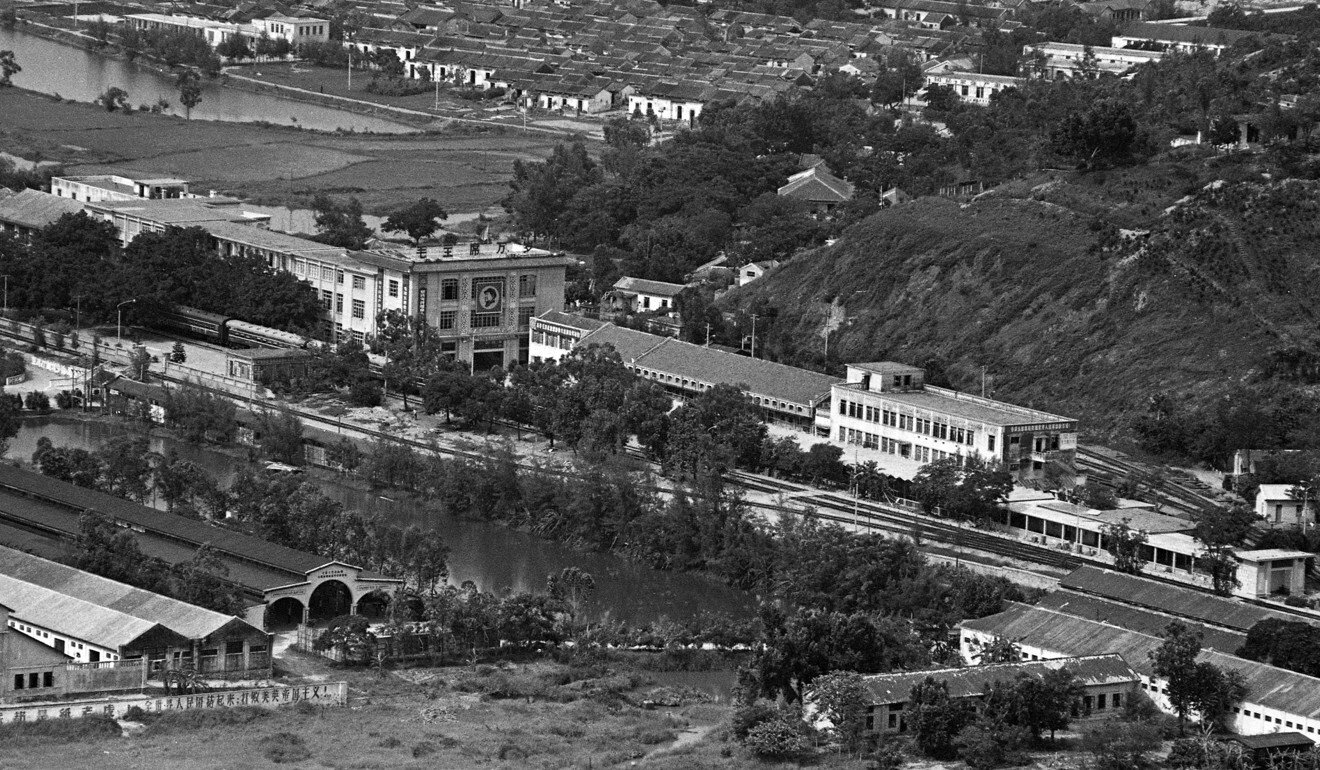

He found himself in a rural backwater. The small 2,153 sq ft factory was in Luohu district, which had only one concrete road.

“None of the buildings in town was higher than five storeys and there was only one restaurant,” he recalled. “Shenzhen officials arranged for me to travel by bus to their office to negotiate the deal because they didn’t have any cars at the time.”

Cheng, 34 at the time, was the first Hong Kong entrepreneur to invest in Shenzhen, then a Guangdong fishing village with a population of 2,000.

Now regarded as the crown jewel of Deng’s economic reforms, Shenzhen owes its transformation in part to the army of Hong Kong industrialists and professionals who headed there in the early days, something state media have chosen to play down or ignore more recently.

The relocation of labour-intensive production lines from Hong Kong proved instrumental in boosting Shenzhen’s economic development over its first decade as a special economic zone.

Cheng had been running his own handbag factory in Hung Hom for a decade before he ventured across the border in 1978. He faced a hard slog turning a small mainland Chinese operation into a production line making handbags for the world.

“All workers were allocated by the government. In the first couple of years, they were assigned to harvesting crops in autumn, just when we were rushing to meet production deadlines for delivering our goods to overseas buyers.”

I persuaded him, promising to go to jail with him if the authorities took action against the factory

Workers were paid a fixed monthly salary of 26 yuan, equivalent to US$39 at the time. “They did not have much motivation to work harder,” Cheng said.

When the workers saw their wages rise substantially as they worked harder, their attitudes changed.

“They resumed work soon after finishing lunch, something they didn’t bother to do when they were paid the same wage no matter how hard they worked,” he said. “Our factory was the first in the Pearl River Delta to adopt piece-rate wage.”

In 1986, the factory moved to bigger premises, from which it churned out 1.2 million handbags and 500,000 pairs of shoes every month. Two years later, it became a “wholly foreign-owned enterprise” with Cheng as the owner.

Nobody went to jail.

The group formed the Association of Experts for the Modernisation of China in 1979 and paid for their own transport and lodging when they crossed the border on weekends and during their annual leave, carrying bundles of lecture notes with them.

Leung, who became Hong Kong’s chief executive in 2012, told the Post last week that getting to Shenzhen in the early days meant going through the only border checkpoint, at Lo Wu, which opened for only eight hours each day.

“Shenzhen officials who greeted us on their side of the checkpoint then gave us grain coupons with which we could buy meals,” he recalled. “The rice we ate was of poor quality. Unlike the white rice we ate in Hong Kong, what we were served was yellow and even black.”

Their living arrangements were basic too. “In those days, the five-storey Huaqiao Hotel was the only place in Shenzhen where a cross-border traveller could stay,” Leung said. “No single or double rooms were available during peak seasons. We once slept on canvas beds along the corridors, near the toilets.”

Despite that, the Hong Kong group was eager to share their expertise with mainland Chinese, who were equally keen to learn.

“It took us two hours to travel from Lo Wu to Shekou, where I was invited to give lectures in a tiny house without any air conditioning,” he said. “There was only an electric fan in the room. Both the audience and I were sweating, but the officials were eager to ask questions.”

In the late 1970s, the association voluntarily drafted a town planning blueprint for Shenzhen with a projected population of 300,000.

In 1988, the National People’s Congress amended the country’s constitution to allow private ownership of land-use rights. Leung helped to draft regulations for Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Shanghai and Beijing, and recommended that local governments use open and transparent means of transferring land-use rights.

Leung set up his own surveying firm in 1993 and went on to become a leading figure in the industry. Currently vice-chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, China’s top advisory body, he marvels at Shenzhen’s growth over the decades.

Looking back at the trips he made with other Hong Kong professionals, he said: “We crossed the border to give lectures and seminars on a voluntary basis and had no intention of seeking any personal benefit.”

By 1988, 70 per cent of foreign investments in Shenzhen came from Hong Kong companies, which accounted for 85 per cent of the total number of foreign enterprises in the city.

Herbert Lun, managing director of his family’s business, Wing Sang Bakelite Electrical Manufactory Limited, recalled the years after his father decided to set up a household electrical appliances factory in Shenzhen’s Shajin district in 1985.

“We needed to send all equipment and spare parts from Hong Kong because Shenzhen’s industrial base was underdeveloped at the time,” he said.

“Hong Kong companies were the first investors in Shenzhen in the early 1980s and hired a substantial number of low-skilled workers there. We helped the city resolve its employment problem at the time.”

Lun, a director of the Chinese Manufacturers’ Association of Hong Kong, said Shenzhen’s success was replicated in other cities in the Pearl River Delta, such as Dongguan and Foshan.

His factory has moved up the value chain by switching from making small household appliances to producing upmarket hairdressing electrical appliances.

It now occupies more than 430,000 sq ft of space and hires nearly 500 employees, down from a peak of nearly 3,000 in 2000. “Thanks to the progress in automation, we don’t need as many workers as two decades ago,” he said.

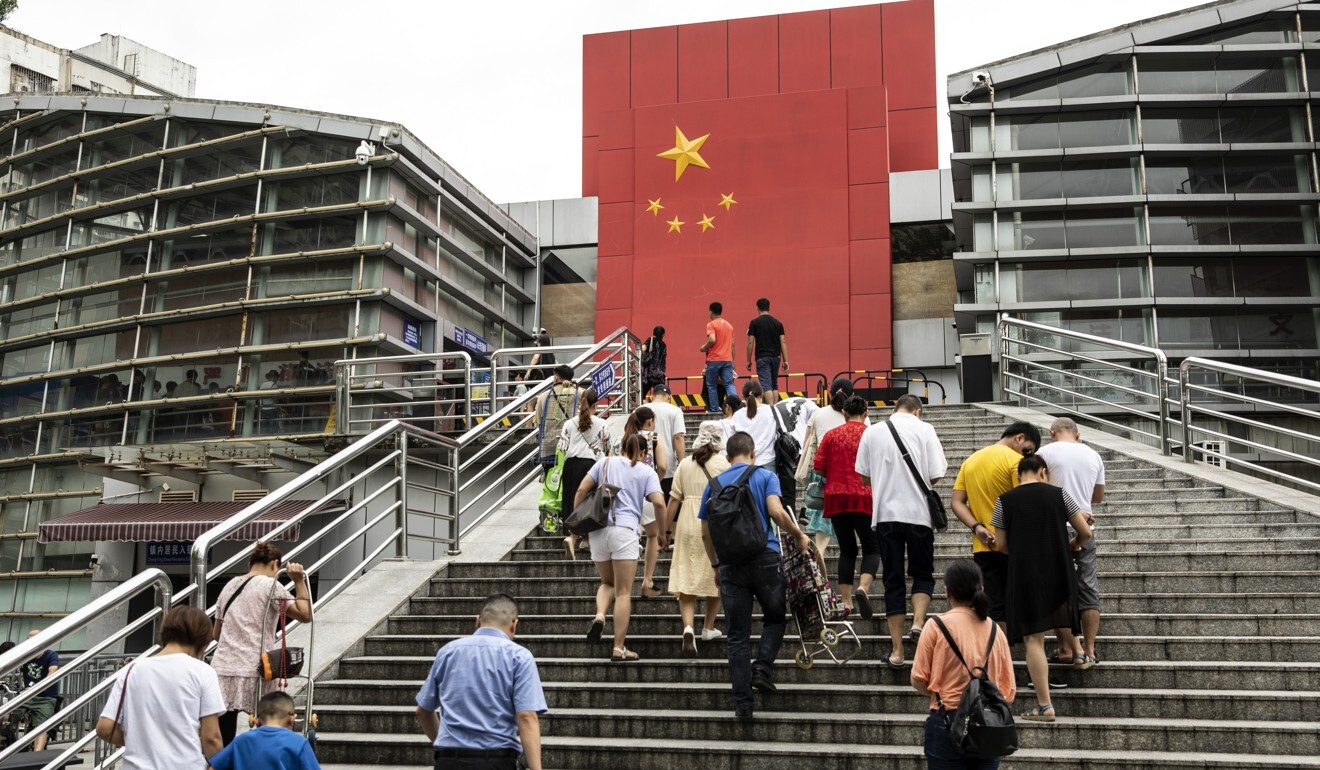

In 2018, Shenzhen’s economy surpassed Hong Kong’s for the first time. In 2019, its gross domestic product was 2.692 trillion yuan (US$389.5 billion) compared with Hong Kong’s HK$2.865 trillion (US$367.4 billion).

Marking Shenzhen’s 40th anniversary as a special economic zone on August 26, the Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily carried a prominent front-page article which did not mention Hong Kong’s role in the southern city’s development.

The omission was unusual, going by previous official publications.

Instead, the 3,200-word article credited Shenzhen’s success to the Communist Party’s decision in 1980 to set up the special economic zone and its plan unveiled in August last year to turn the city into a model of “high-quality development, an example of law and order and civilisation”.

It was left to Yu Youjun, Shenzhen’s mayor from 2000 to 2003, to remind people not to forget Hong Kong’s contribution to the city.

In an interview published last week on the social media account founded by staff of Guangzhou-based Nanfang Media Group, he recalled the words of Deng Xiaoping who said in 1988 that the special economic zone should aim to be a model city representing the country’s pursuit of modernisation.

“The mission was not to create a special economic zone which outdid Hong Kong. What Deng said was to replicate several Hong Kongs on the mainland. He didn’t mean Hong Kong would no longer be needed,” Yu said.

Zheng Tianxiang, a professor at the Centre for Studies of Hong Kong, Macau and the Pearl River Delta at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, said: “In the past two years, some people and officials in Shenzhen have been talking about how the city’s economy has surpassed that of Hong Kong. They should recognise the contribution of Hong Kong businessmen in the past four decades.”

Priscilla Lau Pui-king, adjunct professor of Baptist University’s school of business, said younger Shenzhen officials might not even be aware of the contributions made by Hong Kong businessmen in transforming their city.

She felt it did not matter that mainland Chinese media did not highlight Hong Kong’s role in Shenzhen’s development. “It’s already part of history,” she said.

China’s ‘Silicon Valley’ Shenzhen in line of fire amid US President Trump’s tech war

Forty years on, however, the time may have come for Hong Kong to plug into the prosperity of its mainland Chinese neighbours – not only Shenzhen, but also the other Guangdong cities and Macau, that comprise China’s ambitious Greater Bay Area hi-tech hub.

Zheng sees Shenzhen and Hong Kong developing high value-added industries. “The two cities have potential to collaborate in areas such as Chinese medicine, biotechnology and information technology,” he said.

Guo Wanda, executive vice-president of the China Development Institute, a Shenzhen-based think tank, said the integration between Hong Kong and the bay area was not yet as good as that between Shanghai and the Yangtze River Delta.

“Hong Kong should further facilitate the flow of people and capital among itself, Shenzhen and other cities in the Greater Bay Area,” he said.

Leung Chun-ying said Hong Kong’s strength in professional services still mattered in economic cooperation between itself and Shenzhen.

Citing the plan by Hong Kong and Shenzhen authorities to turn a 87-hectare site at the Lok Ma Chau Loop border area into a technology development zone, he said: “The two cities have lots of room to collaborate in innovation and technology.”

© 2020, . Disclaimer: The part of contents and images are collected and revised from Internet. Contact us ( info@uscommercenews.com) immidiatly if anything is copyright infringed. We will remove accordingly. Thanks!